Hamming Code for Error Correction

A walkthrough on Hamming codes.

- Introduction

- Redundancy

- Parity

- Hamming Code

- Hamming Distance

- Developments in Error Correction Codes

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Digital communication relies on encoded bits that are transmitted across noisy channels which inevitably suffer from errors. This can be a huge problem for systems that cannot deal with errors. An example of this is interplanetary satellites with limited bandwidth and long communication time delays - by the time the effects of an error is detected, it may be too late to send correction commands. Such systems need to be able to detect errors and correct them if possible. A real application of error correcting codes was on the Mariner 9 mission which required pictures to be sent back from Mars1 (this used an error correcting Hadamard code).

This blog will investigate the encoder and decoder stage - how digital information is encoded with error correcting information using the power of numbers. The idea of redundancy and parity is introduced before the Hamming code is described. An example using Hamming(7,4) is given followed by the notion of the Hamming distance. The blog post will conclude with a brief outline of developments since Hamming’s original paper in 1950.

Redundancy

Let the bit length of a message be denoted by $m$. This message can represent $2^m$ unique symbols or characters. If a single bit within the $m$ length bit string is flipped, a different symbol is reconstructed and there is no way of knowing if an error occurred. In order to encode error detection and correction, additional redundant bits are needed. Let the bit length of the redundant bits be denoted by $k$ so the total length of the bits that need to be transmitted is $n=m+k$.

The redundancy factor $R$ is defined to be and this measures the efficiency of the encoding. Redundancy is also a method of generating sparse decompositions of signals and this is known as compressed sensing. This method has applications in computed tomography because image reconstruction can be formulated as a compressed sensing problem2.

A core part of encoding information into the redundant bits is the idea of parity.

Parity

In the context of binary numbers, parity refers to the number of 1’s that appear in the binary representation. Parity can be encoded by a single bit, for instance the $n^{th}$ bit $b_n$, so that the whole bit string $b_n b_{n-1} \dots b_2 b_1$ contains an even number of 1’s. The parity bit is set to 1 if there are an odd number of 1s in the preceding $n-1$ bits, and set to 0 otherwise:

This allows for a single bit error to be detected because if there is a single bit flip, there is no longer an even number of 1’s in the bit string. However, double bit errors cannot be detected. The next step is to add error correcting capability and this is given by the Hamming code (Hamming 1950). The following section will introduce the Hamming(7,4) code which has $n=7$ and $m=4$ (this will have $k=n-m=3$ redundant bits).

Hamming Code

A Hamming code is constructed by assigning the $k$ redundant bits as check bits over select $m$ information bits. If the check bit received in an $n$ bit string matches the computed parity, then a 0 is recorded, and if it disagrees, a 1 is recorded. The sequence of check bits given by $\mathrm{c_k…c_1}$ provides the position of a single error and is called the checking number. If the checking number is zero, then no error was detected. The checking number is required to represent $m+k+1$ combinations giving a condition One can check this condition by substituting $n = m+k$.

For the check number to represent the binary number of the error position, the check bits are placed in positions $1,2,4,8,…,2^{k-1}$. The $i^{th}$ check bit records the parity of bit positions which have a 1 in the $i^{th}$ position in the binary representation So the first check bit will have the parity for bit positions: 1,3,5,7,… which have a 1 in the 1st position. The second check bit will have the parity for bit positions: 2,3,6,7,… which have a 1 in the 2nd position. This is summarised in this Table:

| Check bit | Binary | Check bit 2 | Binary | Check bit 3 | Binary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 100 |

| 3 | 11 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 101 |

| 5 | 101 | 6 | 110 | 6 | 110 |

| 7 | 111 | 7 | 111 | 7 | 111 |

| 9 | 1001 | 10 | 1010 | 12 | 1100 |

| 11 | 1011 | 11 | 1011 | 13 | 1101 |

| 13 | 1101 | 14 | 1110 | 14 | 1110 |

| 15 | 1111 | 15 | 1111 | 15 | 1111 |

Error Detection and Correction Example

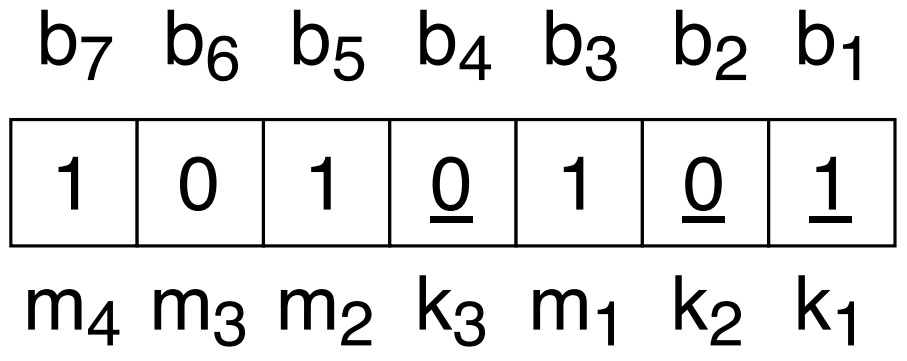

Consider a 7 bit string $\mathrm{b_7b_6b_5b_4b_3b_2b_1}=\texttt{0111100}$ which encodes a bit string ${\mathrm{m_4 m_3 m_2 m_1} = \texttt{b1011} = 11}$ and check bits $\mathrm{k_3 k_2 k_1} = \texttt{b001}$. This is the Hamming(7,4) code meaning $n=7$ and $m=4$.

The original bit string:

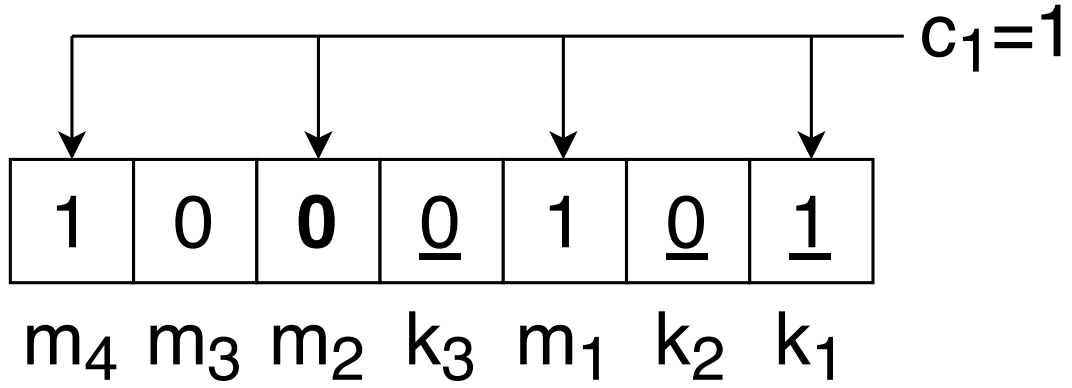

Suppose the bit $\mathrm{m_2}$ in position 5 has an error so instead of the original 1, it is now 0. The checking number $\mathrm{c_3 c_2 c_1}$ can be computed. In Figure 1, the first parity counts an odd number of 1’s in positions 1,3,5, and 7 so $c_1=1$.

Next, the second parity counts an even number of 1’s in the positions 2,3,6, and 7 so $c_2=0$.

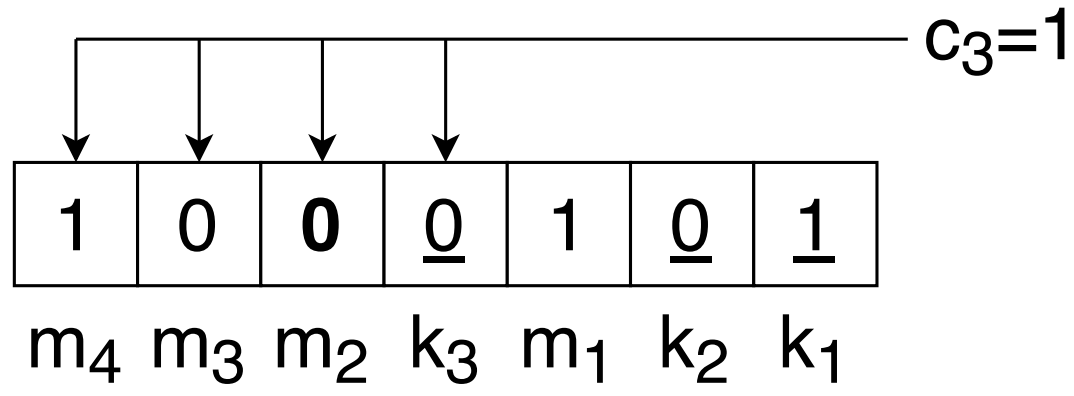

The third parity counts an odd number of 1’s in the positions 4,5,6, and 7 so $c_3=1$.

This gives a checking number $c_3 c_2 c_1= \texttt{101}$ which is position 5. Therefore, there is an error in position 5 which can be corrected by converting the 0 into a 1.

Another example of a Hamming code is triple repetition. Each bit is sent three times and majority rules is applied to decode the message. This is Hamming(3,1) and uses 2 parity bits. Using this code, single errors can be corrected or double errors can be detected but not corrected. This makes sense because if a single bit is flipped, the majority rule recovers the correct bit. However, if two bits are flipped, these errors can be detected but if correction is applied, the wrong bit will be reconstructed. The (7,4) code Hamming introduced in his paper can be extended to (8,4) allowing for single error correction and double error detection.

Single Error Correction plus Double Error Detection

Double error detection can be added by using another bit that represents the parity for positions, that when expressed in binary, have a 1 in the $4^{th}$ position. Then there exists three cases with the first being all parity checks pass. The second case is when there is a single error and the last parity check fails. The checking number then gives the position of the error with zero now meaning the error is in the last check position. The last case is then the last parity check is satisfied but the checking number indicates that there is an error. In this case, there is a double error.

Hamming (1950) 3 gives a way of determining what actions can be done (error detection or error correction) by introducing a metric.

Hamming Distance

The distance $D$ between two bit strings ${x}$ and ${y}$ is given by the Hamming distance.

The Hamming distance is given by the number of positions (or coordinates) where two bit strings differ.

This definition satisfies the conditions for a metric: \begin{split} D(x,y) = 0 \quad &\text{iff } x=y\\ D(x,y) = D(y,x) > 0 \quad &\text{if } x\neq y \\ D(x,y) + D(y,z) \geq D(x,z) \quad &\text{triangle inequality.} \end{split}

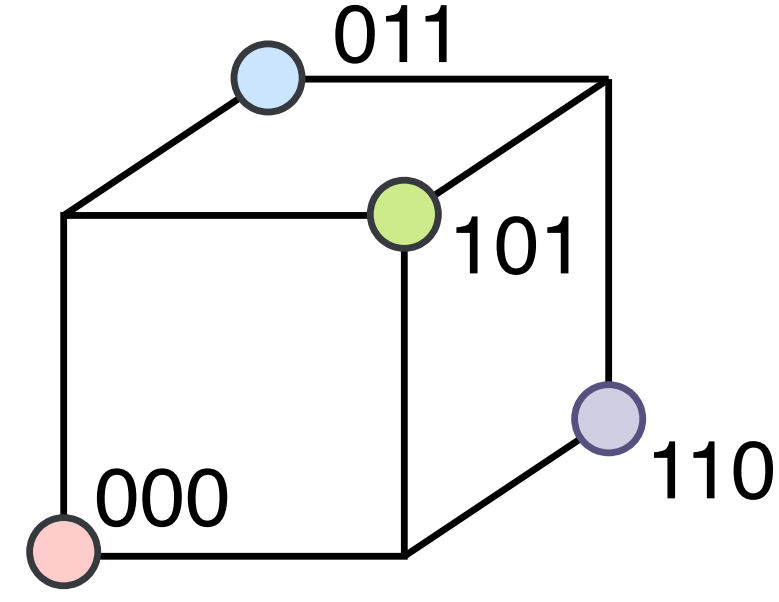

Imagine each code being encoded by corners in a $2^n$ hypercube, then if each code has a distance of $r$ between a neighbouring code, the codes lie on the surface of a $r+1$ sphere centered on some origin. For example, a $r=2$ code with $n=3$ can be: 000, 011, 101, 110. Each code is a distance 2 apart and sit on the corners of a cube as depicted in Figure 5.

When there is a distance of 2 between the codes, then a single error will convert a point on the cube to a coordinate that is meaningless. This corresponds to single error detection. However, this error cannot be corrected since the false code is equidistant to a number of other true codes. A 3 distance code for $n = 3$ can be: 000, and 111. This is shown in Figure 6.

When there is a single error, the error can be corrected because the false code will be closer to the correct code than the others. A more detailed list of actions is summarised in the following table.

| Minimum Hamming Distance | Available Actions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Unique. No redundancy. |

| 2 | Single error detection |

| 3 | Single error correction or Double error detection |

| 4 | Single error correction + Double error detection or |

| Triple error detection | |

| 5 | Double error correction or |

| Single error correction + Triple error detection or | |

| Quadruple error detection |

From the table above, it can be seen that an extra Hamming distance of 2 is needed to correct an additional error and an extra Hamming distance of 1 is needed to detect an additional error.

Developments in Error Correction Codes

More general codes can be made by constructing a parity check matrix which contains error correction abilities based on linear dependent columns4. From there, the mapping between messages and code can be found using a generator matrix computed from the parity matrix5. The example shown in this blog post relied on operations on a Galois (or finite) field with characteristic 2 (so addition and multiplication is done modulo 2). Other fields can also be used such $\mathbf{F}_{11}$ which is implemented in the User Datagram Protocol (UDP). UDP can also fix erasures - when bits are lost rather than flipped6. There is also a family of Hamming codes which include extensions and shortenings that allow Hamming codes to perform better or improve the redundancy factor7.

Multiple error correction codes can be done using Reed-Solomon (RS)8 and Bose-Chaudhuri-Hocquenghem (BCH)9 which can be hard to decode because the number of errors is not known beforehand. By using primitive polynomials for the Galois field, the coding can be done on Linear Feedback Shift Registers (LFSR)10. The location of errors can be found by solving for the roots of an error locator polynomial11 given by the Massey algorithm12. Roots of the locator polynomial are found using Chien search and the Forney formula gives a way of computing the values for erasures13. Following this, Sugiyama invented a method for decoding Goppa codes based on the Euclidean algorithm and Kerlekamp’s key equation, forgoing the need to find the locator polynomial14. Other decoding methods include the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)15.

Many different types of codes exist including cyclic codes and convolutional or continuous codes. For instance, the Chinese remainder theorem is used to decode Fire codes16 which is a type of cyclic code. Convolutional codes can be decoded with the Viterbi algorithm17. Applications of error correcting coding and decoding extend to public key encryption18 amongst others.

Conclusion

The main ideas of error correction codes using the Hamming code were explored with the help of an example. Hamming distance was introduced which gives an indication of what actions can be done depending on the minimum Hamming distance. Finally, a brief overview of developments since Hamming’s paper was given.

References

-

Brian J Thompson, Robert Rennie Shannon, et al. Space Optics: Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of the International Commission for Optics (ico IX), volume 9. National Academies, 1974. ↩

-

Hengyong Yu and Ge Wang. Compressed sensing based interior tomography. Physics in medicine & biology, 54(9):2791, 2009. ↩

-

Richard W Hamming. Error detecting and error correcting codes. The Bell system technical journal, 29(2):147–160, 1950. ↩

-

Robert Gallager. Low-density parity-check codes. IRE Transactions on information theory, 8(1):21–28, 1962. ↩

-

David JC MacKay and Radford M Neal. Near shannon limit performance of low density parity check codes. Electronics letters, 32(18):1645–1646, 1996. ↩

-

Jon Postel. User datagram protocol. Isi, 1980. ↩

-

Victor K Wei. Generalized hamming weights for linear codes. IEEE Transactions on information theory, 37(5):1412–1418, 1991. ↩

-

Stephen B Wicker and Vijay K Bhargava. Reed-Solomon codes and their applications. John Wiley & Sons, 1999. ↩

-

Robert Chien. Cyclic decoding procedures for bose-chaudhuri-hocquenghem codes. IEEE Transactions on information theory, 10(4):357–363, 1964.9 ↩

-

Sybille Hellebrand, Janusz Rajski, Steffen Tarnick, Srikanth Venkataraman, and Bernard Courtois. Built-in test for circuits with scan based on reseeding of multiple-polynomial linear feedback shift registers. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 44(2):223–233, 1995. ↩

-

T-K Truong, J-H Jeng, and Irving S Reed. Fast algorithm for computing the roots of error locator polynomials up to degree 11 in reed-solomon decoders. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 49(5):779–783, 2001. ↩

-

G-L Feng and Kenneth K Tzeng. A generalization of the berlekamp-massey algorithm for multisequence shift-register synthesis with applications to decoding cyclic codes. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 37(5):1274–1287, 1991. ↩

-

Douglas A Leonard. A generalized forney formula for algebraic-geometric codes. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 42(4):1263–1268, 1996. ↩

-

Yasuo Sugiyama, Masao Kasahara, Shigeichi Hirasawa, and Toshihiko Namekawa. A method for solving key equation for decoding goppa codes. Information and Control, 27(1):87–99, 1975. ↩

-

Richard E. Blahut. Transform techniques for error control codes. IBM Journal of Research and development, 23(3):299–315, 1979. ↩

-

R Chien. Burst-correcting codes with high-speed decoding. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 15(1):109–113, 1969. ↩

-

G David Forney. The viterbi algorithm. Proceedings of the IEEE, 61(3):268–278, 1973. ↩

-

Yuan Xing Li, Robert H Deng, and Xin Mei Wang. On the equivalence of mceliece’s and niederreiter’s public-key cryptosystems. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 40(1):271–273, 1994. ↩